mechanical

an exhibition at the

mechMuseum of Modern Art

curated by Jacob Irwin

Instructions

Use keyboard arrows (right, left, up, down) to navigate through slides.

Press the space bar anytime to quickly view all slides as small frames.

Note: This website may not be functional when viewed on monitors that are smaller than 13 inches. Accordingly, if you are unable to view full slides on your screen (i.e., images and/or text is getting cut-off), please open the website later on a device with a larger screen.

MECHANICAL

An exhibition on human achievement in engineering and physical sciences

(selected works of art produced from the first century to present).*

MECHMUSEUM OF MODERN ART: An Online Curated Art Collection

This web app was developed and made public in 2016 by Jacob Irwin.

MECHANICAL

@

mechMuseum of Modern Art

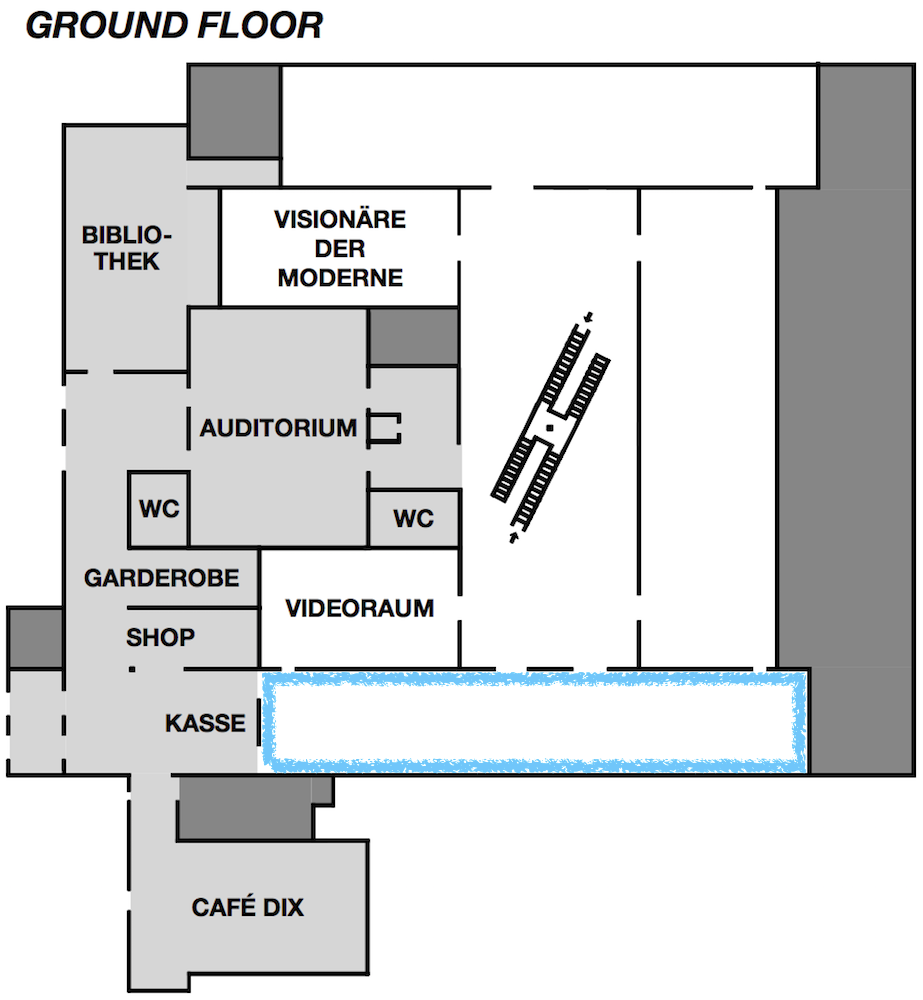

About the Exhibit Space

Ground Floor, Exhibition Area: 200 m² (2150 ft²)

MECHANICAL

@

mechMuseum of Modern Art

About the Exhibit Space (cont.)

Ground Floor (magnified), Exhibition Area: 200 m² (2150 ft²)

MECHANICAL

This specially curated web-based art exhibition attempts to illuminate human achievement in MECHANICAL engineering and the physical sciences as seen through first century to present works of art. Each of the selected works, in their contemporary settings, served to materialize, lest, capture the expanding scientific technologies being interwoven in the societal experience.

This specially curated web-based art exhibition attempts to illuminate human achievement in MECHANICAL engineering and the physical sciences as seen through first century to present works of art. Each of the selected works, in their contemporary settings, served to materialize, lest, capture the expanding scientific technologies being interwoven in the societal experience.

Further exploring aspects of humanity's struggle to understand and, then, manipulate physical forces during their daily lives. That is, in an ever-increasing MECHANICAL universe.

Many of the gifted artists behind these selected works are recognized outside of the fine art as proven engineers, giving double meaning to a display on the MECHANICAL . From Heron of Alexandria's earliest conceptions in 50 CE, through to Merlin's true to life Swanomaton, past Brunelleschi's soaring Florentine Chapel, beyond biblical illuminations, to the more recent lectures on the orrery, the MECHANICAL is an omnipresent force.

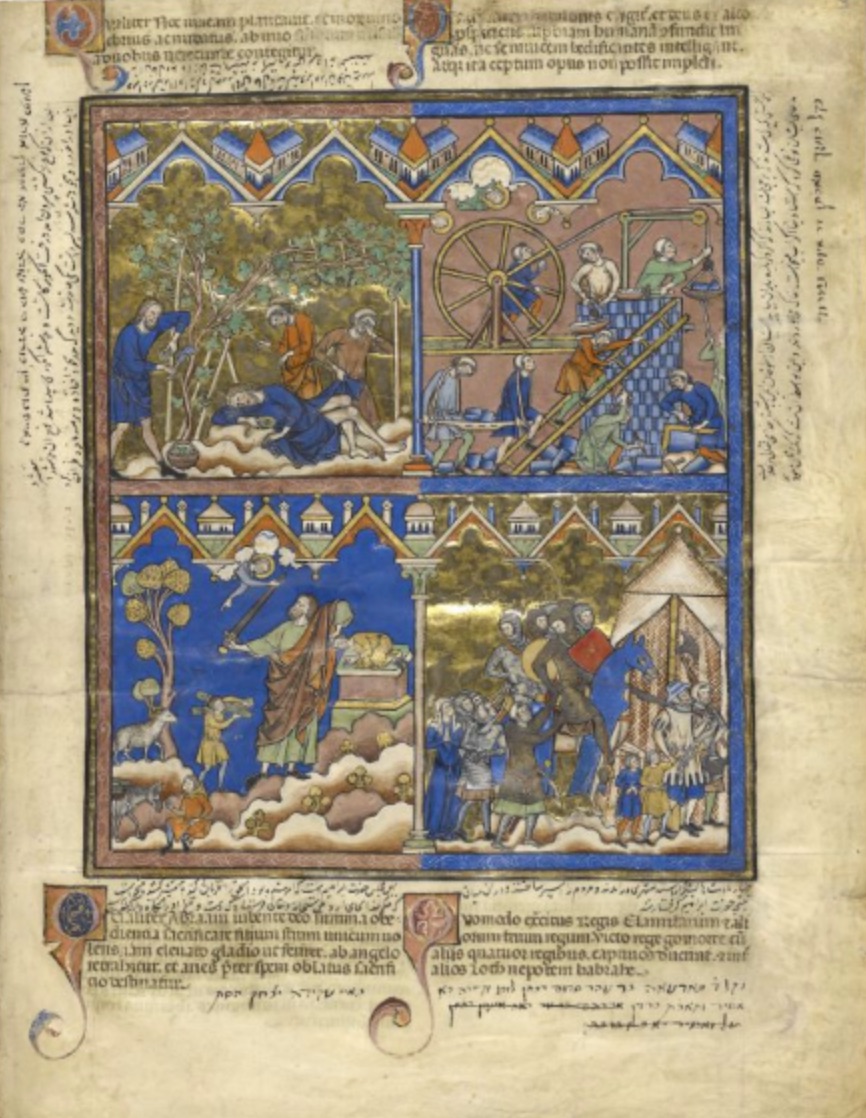

Portrait of female scientist and mathematician, Émilie du Châtelet.

Early MECHANICAL Art

Heron of Alexandria

Untitled, from Pneumatica (Πνευματικά), streaming video

Alexandria, Egypt (ca. 50), Vellum, approx. 390mm x 300 mm.

A hydraulic-powered MECHANICAL device depicts Hercules firing an arrow at a dragon by the Greek Heron of Alexandria (also known as Hero). The work first appeared in Pneumatica (Πνευματικά; ca. 50) as an illustration. Giovanni Battista Aleotti later redraws the diagram as an ingenious device in his 1547 translation of Pneumatica (↓). Aleotti's rendition is nearly identical to Heron's original. Heron captures one of modern humanities' earliest attempts at harnessing scientific knowledge in art. An altar piece, a patron would lift a small apple (located at center on the table top) causing a complex system of water-powered mechanisms to propel the archer's arrow into the hissing dragon's mouth. The pinpoint accuracy of the fired arrow shows a high level of MECHANICAL precision. The device is again reimagined (as seen in the embedded video, above): a proper physical recreation of Heron's mnemonic device by Kostas Kotsanas in 2014 (↓↓).

Early MECHANICAL Art (cont.)

Giovanni Battista Aleotti (in translation by J. Greenwood, B. Woodcroft)

The Pneumatics of Hero of Alexandria

London, England (ca. 1851), Metal print, approx. 100cm x 70cm.

Early MECHANICAL Art (cont.)

Kostas Kotsanas

A reconstruction of Heron of Alexandria

Web (ca. 2014), Hydraulic mnemonic, 1.6m in height.

Early MECHANICAL Art (cont.)

The hydraulic automatic of Hercules the archer and of the dragon’s hiss, additional: external museum link to related Heron automata information

A MECHANICAL Beauty

John Joseph Merlin

Silver Swan

Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, England (ca. 1773), Automaton made of silver, 1.8 m in height.

Behold the most lithesome automaton ever crafted... in 1773, Merlin outdoes his contemporaries with a Silver Swan. The Swan comes to life with vibrant neck extensions and swivels while intricately crafted fish swim in water (atop oscillating glass rods) near the base. Built almost entirely of silver, the precious metal is complimented by reflective glass. Meanwhile, thousands of hidden levers and small moving parts give life to the mechanical animal's movements.

Merlin's masterpiece... it features both ingenious clockwork engineering and visionary artistic flourished. By using clockwork to drive simple glass cylindrical rods, Merlin was able to mimic the extraordinary complexity of moving water. As the light catches the twisted and imperfect surface of the rods it creates the unmistakable reflection of water on the underside of the swan. (Simon Schaffer)

A MECHANICAL Beauty (cont.)

John Joseph Merlin

Silver Swan

Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, England (ca. 1773). Automaton, 1.8 m in height.

MECHANICAL Heights

Filippo Brunelleschi

Duomo di Firenze (English Translation: Florence Cathedral)

Florence, Italy (ca. 1420—ca. 1436). Marble, brick, 114 m in height (exhibit framed photo: 3 m x 2.1 m).

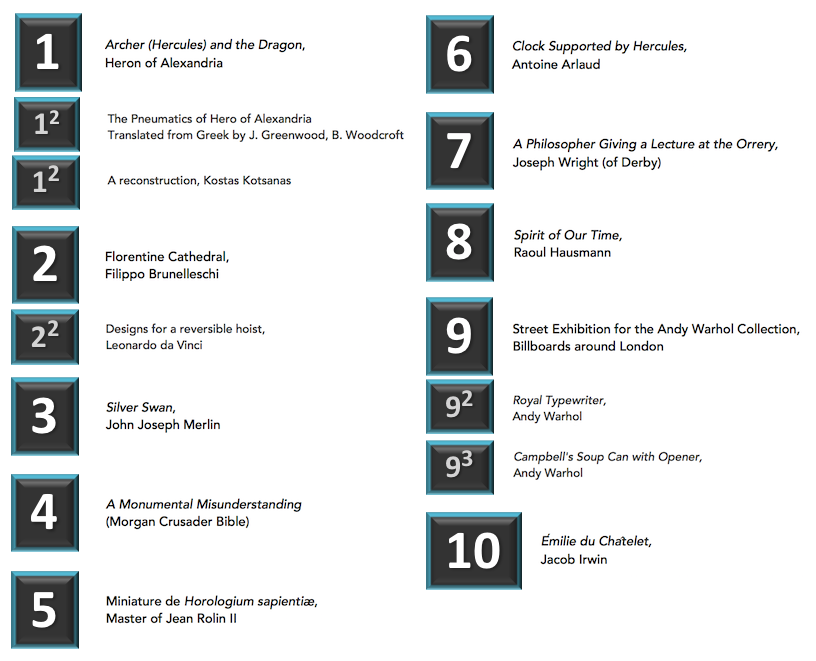

Arnolfo di Cambio began work on the Florence Cathedral in 1294 and the copper sphere was placed on the top by Verrocchio in 1472. The Florentine basilica-style cathedral is often attributed to Filippo Brunelleschi, a key architect behind the integrative components—with its fish bone skeleton—it was a jointing game suited best for this qualified master. "Brunelleschi had rediscovered or invented the constructional laws of the ancients, laws being taken to mean both their technical expedients and their 'musical proportions'. (Harvard.edu, pg. 100.)" Leonardo da Vinci would later go on to study various aspects of the cathedral whilst a student. Leonardo would conceive the reversible hoist (↓) based on his studies of Brunelleschi's hoist system used in the construction of the Florence Cathedral.

No known lifting mechanisms were capable of raising and maneuvering the enormously heavy materials. He invented a three-speed hoist with an intricate system of gears, pulleys, screws, and drive shafts. It used a special rope 600 feet long and weighing over a thousand pounds—custom-made by shipwrights... a groundbreaking clutch system that could reverse direction... Leonardo from the nearby Tuscan town of Vinci, whose sketchbooks tell us how they were made. (National Geographic)

MECHANICAL Heights (cont.)

Leonardo da Vinci

Reversible hoist: det., Codice atlantico, fol. 1083v/391v-b

Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milano, Italy (ca. 1490). al print, approx. 29cm x 20cm.

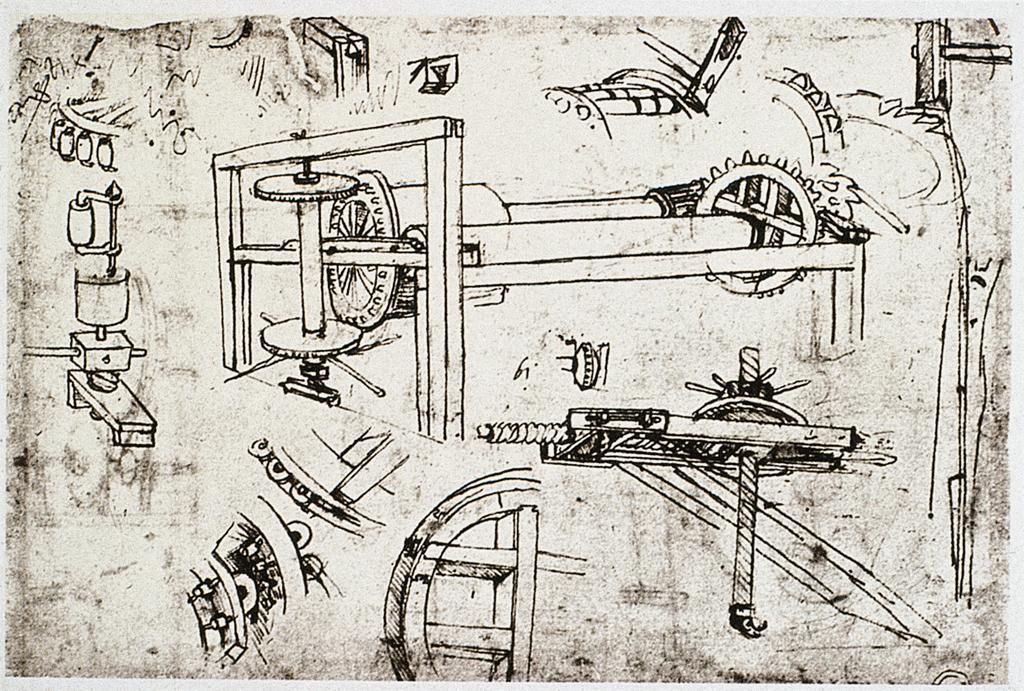

RELIGIOUSLY MECHANIZED

Miniature in the Morgan Crusader Bible

A Monumental Misunderstanding from fol. 3r, Old Testament miniature

Austrian National Library, Wien, Austria (ca. 1230). Facsimile of vellum (illuminated, disbound), 390 mm x 300 mm.

Early in the thirteenth century, laborers created and implemented building projects using modern mechanics, as shown in this 1240s biblical miniature A Monumental Misunderstanding. The Lord halted their plans – not because of the of invention of the pulley system – because to build a tower that reaches to the heavens was intended. (Genesis 11:3-4)

RELIGIOUSLY MECHANIZED (cont.)

Leaf in the Morgan Crusader Bible, fol. 3r

Noah in His Cups; A Monumental Misunderstanding; The Greatest of Tests; Lot Taken Captive

Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, NY (ca. 1916). Facsimile of Old Testament miniature on vellum (illuminated, disbound), 30cm x 40cm.

Purchased by J.P. Morgan (1867-1943) in 1916, the integration of mechanical tools into the daily lives of human society are depicted in this precious illumination. Notably, weapons/weapon technology appears (in the lower-half miniatures: The Greatest of Tests and Lot Taken Captive).

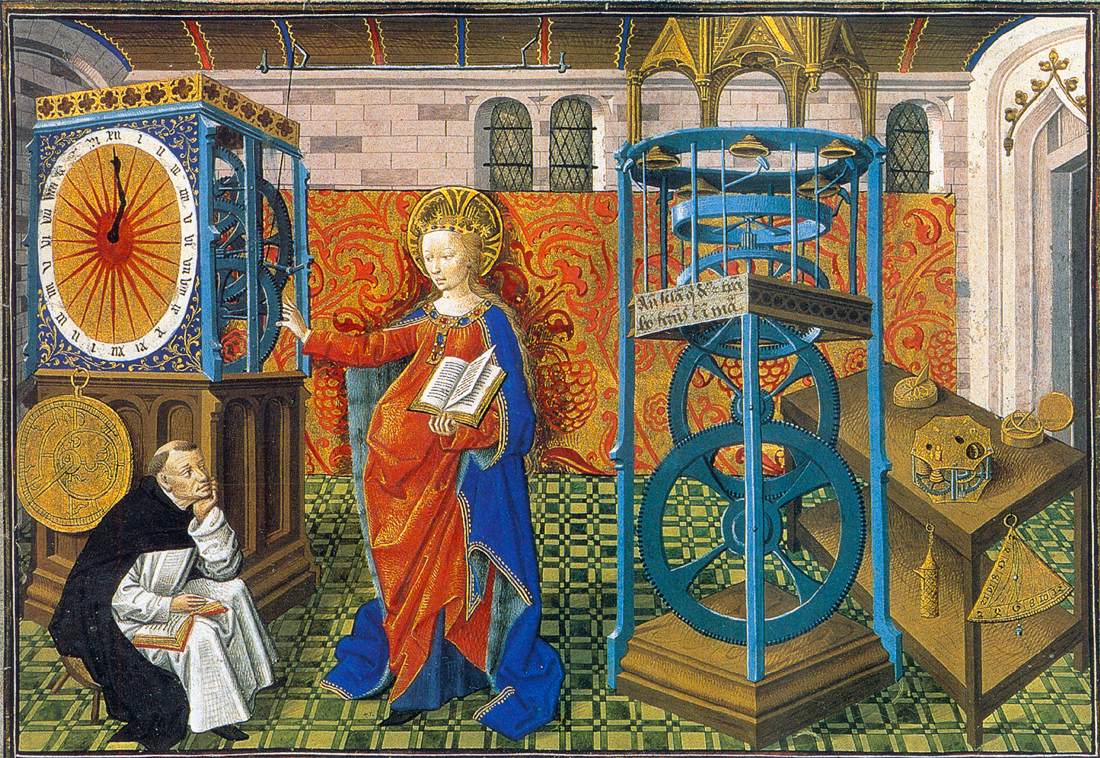

A MECHANICAL Vers

Master of Jean Rolin II

Miniature de Horologium Sapientiæ vers

Bibliothèque Royale Albert (Royal Library of Belgium), Bruxelles, Belgium (ca. 1455). Velum, illuminated, approx. 24cm x 16cm.

This illumination depicts humans operating machinery in the 14th century. Illumination by Master of Jean Rolin II, original by Constance Henrich Seuse (alias Henry Suso; German Dominican in 1334).

The miniature on folio 13v shows an exhibition of 14th-century clocks. The two characters are the Dominican author, Heinrich Suzo (c. 1295-1366), and Lady Wisdom. The clocks, from left to right, are an astrolabe, a clock, which chimes the hour by pulling a rope running through the ceiling, a large MECHANICAL clock with five bells and four smaller clocks on the table (WGA).

MECHANICAL CLOCKWORK

Antoine Arlaud

Clock Supported by Hercules

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland (ca. 1580-1600). ded brass, silver, steel and brass movement, 26.8cm in height.

In the 1500-1600, due to the circular and regulated motion, clocks were associated with the motions of the universe. Hercules, bearing the weight of the universe, is demonstrating the minute details and intimacy of time, seasons, and heavens. The universe, or the clock, is the revolving heavens in this piece. A second, much smaller Hercules, sits atop the clock, holding a club.

A School for MECHANICAL Philosophy

Joseph Wright (of Derby).

"A Philosopher Giving a Lecture on the Orrery"

Derby Museum and Art Gallery, Derby, England (ca. 1766). Oil on canvas, 147cm × 203cm.

An orrery illuminates Wright's canvas, captivating faces of admonishing youth—shown witnessing heavenly events. The mesmerizing center piece is a significant shift display of science – bringing technology and religious subject matter onto the canvas (ca. 1730).

As scientific curriculum found its way into the aristocratic educational system, and after the Royal Academy had celebrated its Centenarian, Wright brushes luminous oil colors, shining a light on the instrument of the day: the perfected orrery. A MECHANICAL model of the solar system with asynchronous moving parts—here, we observe an orrery in the round. The dimensionality of the painting engages with the physical, as if reaching inside the outer frame of the expansive orrery and back out as a shimmering spectacle—curious is at least one young man about how the MECHANICAL moving pieces are able to keep pace.

MECHANICALly Human

Raoul Hausmann

Spirit of Our Time (Mechanical Head)

Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France (origin: Germany; ca. 1921). Combine, 32.4cm in height.

This MECHANICAL Head is a mannequin sculpture created in Germany. A sculpture of sorts, which is littered with the tools of the engineer, else, craftsman. Each accessory attached with purpose, without conformity—the work combines a hairdresser's wig-making dummy, crocodile wallet, ruler, and pocket watch mechanism (amongst other materials)—attached to wooden human-like head sculpture. Creator Hausmann, shows the materials, including a wallet, ruler, camera components, pocket watch mechanism and ruler in a provocative display during the Dada art movement.

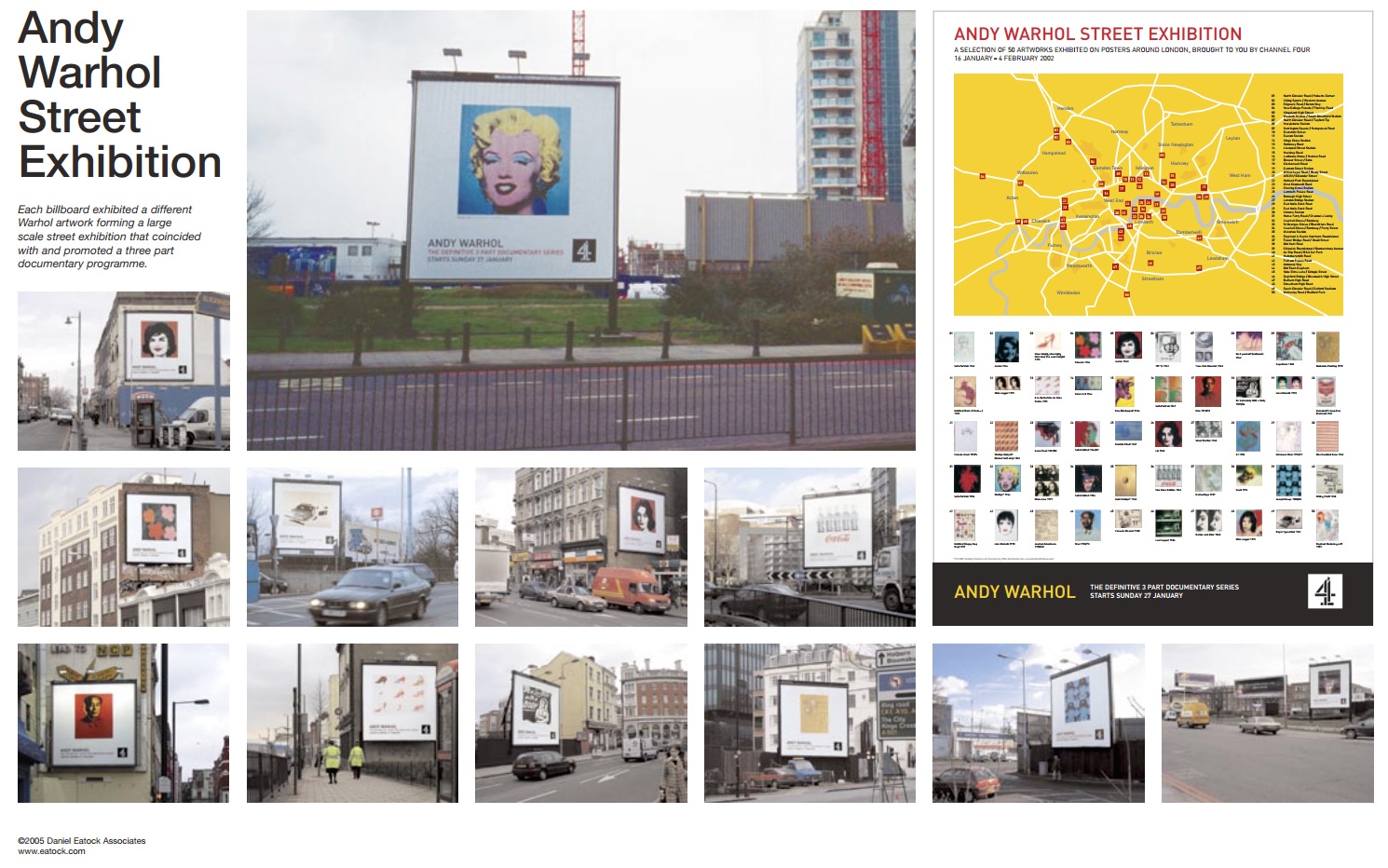

MECHANICAL Imprint

Andy Warhol

Royal Typewriter on Billboard

London, England (ca. 2002). Metal print, enlargement, 70cm x 50cm.

The typewriter—MECHANICAL in its very nature and as a Warhol pop art product. The Royal Typewriter is imbued in its truest black and white form, in 1961, during an era of maturing printing processes.

Warhol left an indelible imprint on London (2002), where billboards of his work are scattered throughout the Big Smoke polis. Actual size: 8 m x 8 m, the Billboard of Warhol's Royal Typewriter in the Andy Warhol Street Exhibition, Billboards around London was an unique approach to sharing art, made possible through Warhol's silk-screening technique that produced colorful works, which are visible at a distance (and quickly understood), as pictured in Eatock & Associate's Portfolio, an enlarged metal print shares information about an exhibition that was on display around the city from January 16, 2002—February 4, 2002. Smoke aflutter—given off by motorized vehicles abound—lends evidence to the pervasive nature of modern industrialized MECHANICAL societies.

MECHANICAL Imprint (cont.)

Andy Warhol

Royal Typewriter on Billboard

London, England (ca. 1961). Metal print, enlargement, 70cm x 50cm.

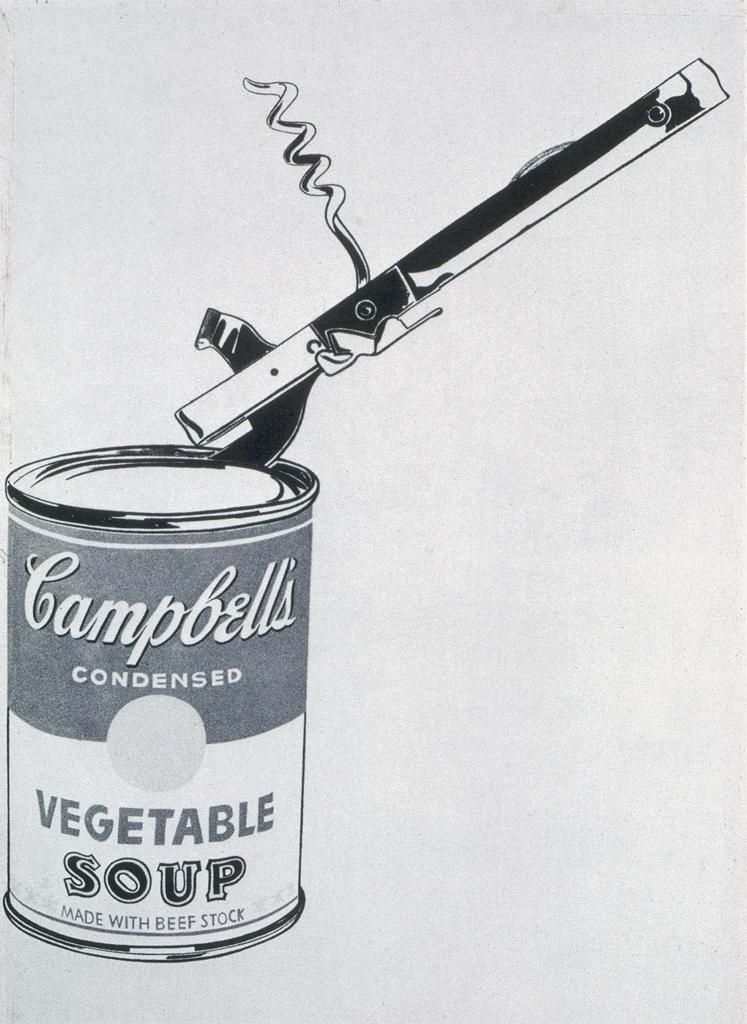

MECHANICAL Imprint (cont.)

Andy Warhol

Campbell's Soup Can with Opener

United States (ca. 1962). Print, 1.8 m x 1.4 m.

Warhol's Campbell's Soup Can with Opener puts MECHANICAL quite literally onto the canvas. A sharp can opener is visible piecing Warhol's beloved Campbell's Soup can. Warhol's process of transfer ink from one medium to the next perfected to bold MECHANICAL lines, as can be seen powerfully defining the can's top edges.

MECHANICAL Women

Jacob Irwin

Émilie du Châtelet

New York, NY, USA (ca. 2016). Metal print, 50cm x 70cm.

Émilie du Châtelet was the first to translate Isaac Newton's 1728 work, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica), into French (the same version still used in France today). Châtelet created experiments of her own based on the Newtonian physics she consumed during her translation work. In a famous 18th century portrait painting of Voltaire's mistress by Maurice Quentin de La Tour (image visible on the introduction page; near top), Châtelet can be seen delicately and articulately fingering a compass atop the works of Newton. A gifted mathematician in her own right, Châtelet represents the contributions of women scientists throughout history.

MECHANICAL Women (cont.)

Jacob Irwin

Émilie du Châtelet

New York, NY, USA (ca. 2016). Metal print, 50cm x 70cm.

This is the original conceptual drawing (drawn with pencil on paper).

MECHANICAL God

Anonymous

God as Architect/Builder/Geometer/Craftsman, The Frontispiece of Bible Moralisee

France (ca. 1220). Illumination on parchment, 34.4 × 26cm.

Discover more: https://www.dartmouth.edu/~matc/math5.geometry/unit10/unit10.html#the ptolemaic universe and http://www.rosaryworkshop.com/RBS2-GodTheGeometer.html

Related illumination: http://www.luminarium.org/encyclopedia/godgeometer2.jpg

maritimeMECHANIC

Stanley Meltzoff

John Harrison perfecting his marine chronometer No. 1 in 1735

Oil on canvas.

John Harrison (3 April 1693– 24 March 1776), English clockmaker whose marine chronometer solved the problem of accurately establishing longitude at sea, revolutionising maritime navigation.

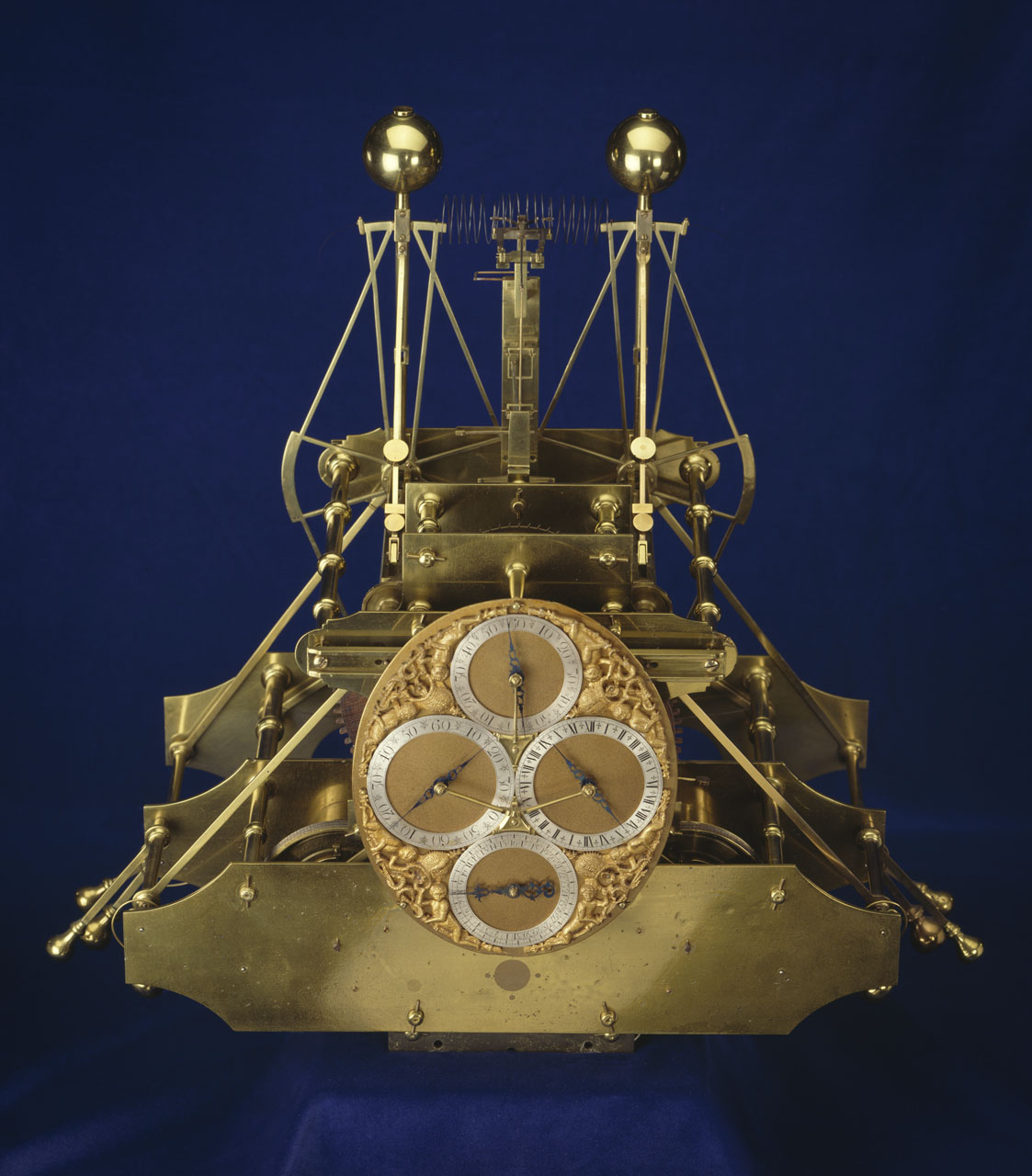

maritimeMECHANIC (cont.)

John Harrison

John Harrison's invention, the marine chronometer No. 1.

Mechanical device (ca. 1735).

John Harrison's marine chronometer, which solved the problem of accurately establishing longitude at sea.

← back to beginning of exhibit

Thank you for viewing MECHANICAL

*: MECHANICAL is not a real exhibition.

Special thanks to Hakim, creator of reveal.js

Project submitted to Dr. Jack Hartnell—Spring 2016

Columbia University—Masterpieces of Western Art (HUMA1121)

Sources for all images, slide down ↓

Works Cited

click here to view all bibliographic source information (for this entire virtual art exhibition)

Gallery END ■